- Home

- John Benteen

Sundance 4 Page 9

Sundance 4 Read online

Page 9

“No, thanks,” Wade said. “I’d rather make the haul.”

Roane let out a long breath. “I was tryin’ to do you a favor.”

“You know what you can do with your favors,” Wade rasped.

Roane stiffened in the saddle, then relaxed. “Suit yourself,” he said thinly. “Come on, men.” He jerked the bay around, spurred it hard. His punchers galloped after him. Sundance and Wade turned to watch them go.

After a moment, Wade said, “I see what you mean, Sundance. There ain’t but one reason Roane could be ridin’ for Hell, Yes! There’s no supplies to buy there, nothin’ he needs there—except a lot of men who hate my guts.” His face was hard. “Easy for him. He can find plenty of men there who’d like to wipe me out. You, too. Then he’s in the clear, they take the blame; he gets his land back ... and maybe Susan along with it. Yeah.” His hand tightened on the Winchester. “Yeah, I’ve got a feelin’ it won’t be long before I need this gun.”

Then he sat down on the wagon seat, gathered up the lines. “Hi-yaa!” he yelled to the horses and lashed them into a trot with the rein-slack. The wagon rumbled toward the ranch, Sundance galloping ahead, keeping close watch on the hills around them.

Somewhere in the distance, a wolf howled. Closer by, a calf blatted. The moon rode high above the lava beds to the south, as Sundance moved through the trees along Lost River like a wraith, a wisp of fog, soundless and nearly invisible. The quiver of arrows was on his back, his bow in hand. They were good weapons for a nighttime scout, soundless, flameless; and he was capable of shooting arrows almost as swiftly as he could work a Winchester or a Colt.

Even as he entered the ranch yard, he was still alert. He made an inspection of the outbuildings, circled the hay wagon parked near the back door. He checked every pool of shadow, every hiding place that might have concealed a man. Then he went to the door, rapped on it softly.

“Who is it?” Wade asked cautiously.

“Sundance.”

The door opened. Sundance slipped into the kitchen, closed the door behind him. Wade held a candle in one hand, a pistol in the other. When Sundance was inside, he blew out the candle. “See anything?”

“No. All quiet.”

From the living room, also dark, Susan Wade said, voice taut, “It’s nearly two. If they’re coming, shouldn’t they be here by now?”

“It’s a long trip from the lava beds,” Sundance said. “And they’ll travel slow, careful. They may not get here until just before first light.” He found his way to the stove, poured a cup of coffee from the pot there. “Susan, you can go on to bed. Glenn and I’ll keep watch.”

“No. No, I couldn’t sleep. I’ll sit up with you.”

“Suit yourself,” Sundance said. He went to the window, stood not before it, but to one side, cautiously looking out. He was pretty sure the Indians would not come to the front door. He had checked the cover, and it was better behind the house. He knew how Nehlo would travel, using every bit of concealment possible, could almost prophesy which trees, bushes, outbuildings he would choose as cover. He sipped the coffee, thinking about what lay ahead. Even though the Modocs lived in the Cave of Ancient Pictures, he was pretty sure they remained unaware of the secret offshoot of it Kintpuash had spoken of, and of the presence of the gold there. The cave was a sacred and somewhat fearsome place, and it was not likely they would poke around in its depths. The chances were that the gold still lay exactly where Jack’s father had put it.

If the Modocs came in, it would take a few days to haul them out, get them safely underway to the Wallowa, then return to Wade’s ranch. After that, he could poke around the lava beds all he pleased, searching for the cave. When he had the gold, he would smuggle it out, say goodbye to the Wades, head east with it. He could not stop the Modocs in the stockade at Fort Klamath from being transported to Indian Territory, but once they were there, he could put the gold to good use to see that they were well resettled, that each family at least had decent clothes and tools to use to farm with, a way to make a living. Then, he thought, he had some business with the generals—Sherman and Sheridan. Once he had got Nehlo’s wife to him, that was the next order of things.

The Modoc War, he knew, had cost every Indian in the west more than the tribes could afford to lose.

The spectacle of a few Indians making fools out of a thousand soldiers had aroused the Army to ferocity. A public laughingstock, from now on it would seek battle with Indians wherever battle could be found, to erase the blot on its honor. And it would provoke and crowd the tribes until they had to fight, and when they fought, it would do all in its power to exterminate them.

Sundance drained the coffee cup. Damn it, he thought, if only they hadn’t transferred Crook! Until three years ago, he had been commander of the Department of the Columbia, the post to which the slaughtered General Canby had succeeded. And George Crook was the only general in the Army who had any real liking or respect for Indians and talked to them and tried to learn their customs and anticipate their grievances. He would have worked out something for Kintpuash and a lot of men now dead would still be alive.

Well, Crook was in Arizona, but Sundance could still talk to Sheridan and Sherman, top men in the Army. Until now, through his friendship with them, he had been able to exert a restraining influence. They were no Indian-lovers, they saw Indians only as the enemy, but they were practical men, and he had given them practical advice, and he had earned their trust for that. He had been able to hold them back a little, and his suggestions had prevented bloodshed on both sides; and they knew that. But the Modoc War had changed things: this obscure band of hunters and gatherers and diggers had, Sundance knew in his bones, altered the history of the West. Sherman and Sheridan were, above all, soldiers, Army men; and the Army they loved had been humiliated and beaten. Now they would be desperately trying to wrench authority to deal with the Indians away from the civilian Bureau of Indian Affairs; they would be in a mood to exterminate every Indian who came within rifle range of a soldier. And he would have to try to explain the consequences of such a policy to them, and what it would cost everybody, and he doubted now that they would listen.

Sundance tensed, set the coffee cup aside.

In the distance, a wolf howled again.

He kept his eyes focused on the pool of shadow behind the barn. Maybe it was only a trick of light, but it seemed to him that something moved there. And if he had been an Indian trying to reach this house, that was where he would have paused before making the last dash to the shelter of the hay wagon.

“Sundance—” Wade began.

“Be quiet,” Sundance said. He still watched the shadow.

Again, he was certain of movement. Then they came out, crossing the moonlit open space between there and the wagon at a dead run, bent low. Five of them, shadows themselves, and so briefly exposed in their passage that if he had merely blinked, he might have missed them. Then he knew that they were behind the wagon. Wade said, “What—”

“Hush,” Sundance said. “They’re coming in.” He went to the back door, unbarred it, opened it. Then he said, in Klamath: “Come, my brothers. The way is safe.”

For a moment, nothing moved in the blackness behind the wagon. Then a single form loped forward, rifle at the ready. Sundance stood exposed and vulnerable in the doorway. As that crouched shape neared the steps, he recognized it: Nehlo. Then the Modoc leaped in a single bound into the kitchen. Gun up, he pressed his back against the wall, and the whites of his eyes shone as he looked around.

“It’s all right,” Sundance said. “No one here but me and the Wades.”

“I’ll take a look,” Nehlo said in dialect. He shoved past Sundance into the front room. His eyes probed the shadows. Then Sundance heard the breath of relief that came from his barrel chest.

He turned, lowering the rifle. Without words, he strode to the door, gave a low whistle. Then they came, the other four: Chachisi, Beneko, and their women. They scurried through the door, the men with ready guns, an

d Sundance closed and barred the door behind them. “Welcome, brothers,” he said. They only looked at him with a mixture of fear and suspicion: wild things cornered.

Sundance said: “We have coffee and there is meat to eat. We are glad to see you. Eat first, then we’ll talk.”

“No,” said Nehlo. “We’ll talk now.” He went on, in English. “We’ve come, that don’t mean we’ll stay. You tell us your plan.”

“You saw the hay wagon. Come morning, you’ll be hidden in the hay. Wade and I’ll roll the wagon northeast, up into the desert. When we’re away from people, we’ll give you horses, whatever else you need. You can ride up to the Wallowa River, and I’ll send a letter with you to Joseph. If you keep a sharp watch, you won’t even meet anybody on the way—that country is empty between here and there.”

Chachisi said, “That’s true. I know the way to the Wallowa. No trouble, once we’re out of Lost River country.”

“Maybe, maybe not,” Nehlo said, face still suspicious. “I still am not sure . . .”

“Listen,” Wade said. “All we’re after is to save you.”

“Perhaps. But—”

“Look.” Wade picked up an oil lamp. “I’ll light this and you can look around. Be sure we’re alone.”

“You don’t light any lamp,” Sundance rasped. “They can see in the dark. So can I. I’ll feed ‘em. Then they can get in the wagon, and we’ll roll right away.” He turned to the stove, took a pot of venison from it, set it down in the middle of the table. “Eat,” he said. “Fast. Every minute counts.”

Nehlo stared at the food. Then he said, backing away, “The rest will eat. I will stand guard.”

“Suit yourself,” Sundance said. He put out plates and spoons. The Indians poured stew on the plates, ate like wolves. They did not sit down, only hunched over the food and shoved it in their mouths with gobbling sounds. While they did that, Sundance appraised them. They had brought nothing with them but the clothes they wore and the weapons they carried. So he had been right. They had not known about or found the gold.

When the other four were through, Nehlo cautiously advanced to the table. “Chachisi, Beneko. Keep watch now, and I will eat.” He reached for the pot.

And from outside, not far away, a rifle thundered as a slug hit the pot and tore it from Nehlo’s hands.

Chapter Seven

Window glass, bullet-smashed, sprayed Sundance as he reeled aside. The stewpot, wrenched from Nehlo’s hands, slammed against the wall and spilled. As the Indians stood frozen, more guns thundered, and suddenly the kitchen was a hell of screaming lead.

Sundance yelled: “Down!” He threw himself across the table, lead whining all around him, and knocked the Modoc to the floor. Nehlo hit hard, but his wiry body writhed and twisted.

“You son bitch!” he gasped in English. “Rotten ambush! Damn ambush to kill us all!” He jerked his rifle around.

Sundance hit him hard, and as his fist smashed into Nehlo’s chin, the Indian sighed and went limp. Sundance grabbed his rifle, rolled off and across the floor, yelling: “Glenn! Get Susan under the bed, behind the mattress!”

“Already done it!” Wade bellowed back. “It’s Roane and that Hell, Yes! crowd; got to be!”

Chachisi had seized his rifle. “Sundance!’ he rasped. “You’ve betrayed us!” He lined the gun.

“No!” Sundance yelled. “No, wait! Get your women down! It’s not you they’re after, it’s Wade and me! Get down!”

Chachisi did not move, though the women were already flat on the floor, and Beneko with his rifle was behind the iron stove, off which bullets screamed viciously as whoever was out there in the darkness poured the fire of many guns into the house. “Listen—” Chachisi yelled, and Sundance saw his finger tightening on the trigger, his face wild, confused. “Listen, you—”

Then the incoming slug hit the gun. It smashed into the barrel just before Chachisi could fire at Sundance, jerked the rifle from his hands. Chachisi spun around with the impact. Sundance was on his feet instantly. There was no time to argue. He had to fight the people out there, not Indians in here who thought they’d been betrayed. He brought down the barrel of Nehlo’s rifle, and it made a solid thunk! when it connected with Chachisi’s head. The Indian crumpled, and as Sundance rolled aside, Beneko fired at him from behind the stove.

He had expected that, which was why he had twisted, and the slug went by. Then he whirled on Beneko with the gun, and before the man could get another round into the weapon, had the rifle up against his throat.

“You!” Sundance rasped, as lead whined over him. Wade was shooting back through a window. “Those men outside are our enemies—mine and yours alike! They want to kill us both! All of us have got to fight against them! This is no trap, you fool—” He broke off as a bullet ripped his cheek.

Beneko stared at the blood oozing down. “No,” he rasped. “No, I see that. Who are they?”

“White men who don’t even know you’re here! It’s Wade and me they want! If they kill us, you’ll never get free!” He threw himself flat behind the stove as more slugs ricocheted. “Wade and I’ll try to stand ‘em off! You watch Chachisi and Nehlo! When they come to, explain, don’t let them shoot us. Fight with us, and we’ll get you to Chief Joseph.” His mouth tightened in a wolfish grin. “Or die beside you!”

Beneko met his eyes. Then he nodded. “All right. I understand. I’ll make them see.”

“Good.” Sundance lowered the gun, laid it across Beneko’s knees. “Give it to Nehlo when he comes to. I’ve got a weapon of my own.”

There was a second when, if Beneko disbelieved him, the Modoc could have killed him easily. Sundance took that chance. He did not even look back as he snaked across the floor on which the women lay flat, under a deadly rake of fire, to his own Winchester.

Like a snake, he slithered to the front room. Fire was coming from all quarters now. The men from Hell, Yes! and maybe Roane and his riders, too, were out there, surrounding the house. Wade was beside the window on the right, pumping Winchester slugs at the gun flashes in the trees on that side. Sundance crawled to the one on the left, stood up and, sheltered by the jamb, looked through.

In the trees beyond the yard, he saw the wink of gun flames. Fifteen, maybe twenty men from Hell, Yes! out there around the house, he guessed. And he and Wade and three Modocs who were confused, suspicious, and could not wholly be trusted—not much of a force to stand against them. Sundance poked his rifle through a broken window pane, mouth twisting. Well, he had faced longer odds before. He saw a gun-flash, heard the whine of lead, waited, and when the flash came again from the same spot, was ready and pulled the trigger. Above the roar of gunfire, he heard a man scream and laughed softly. Then he looked for another target.

He found one, again waited out two flashes and pumped a bullet to their source. Nobody hollered then, but there was no more shooting from that place, either. Still, though, the house was a hell of screaming lead, and now, from outside, a voice bellowed. “Wade! Sundance!”

He recognized it: Archie.

“Wade!” it bawled again. “We don’t wanta kill your woman! You and Sundance give up and we’ll let her go! It’s you two we gotta have!”

Wade made a sound in his throat. “You bastard!” he yelled back. “You think I’d let your crowd get your hands on my woman alive? You go to hell!”

“All right! It’s on your own head, then! I got twelve guns out here, and we ain’t gonna stop until you’re all buzzard bait!” A pause. Then he roared: “Let ‘em have it, boys, and don’t slack up!”

Now the fire redoubled, and lead chopped the boards of Wade’s house and screamed off of everything metal: stove, bedstead, even the water bucket. The coffee pot went sailing across the room. Splinters flew and glass shattered. Sundance recoiled from the window before that deadly sleet. Susan Wade cried out, but whether she was terrified or hit he could not tell.

Then something touched his elbow. He turned to stare into the stolid, slit-eyed face of Nehlo

. Both flinched involuntarily as heavy slugs chopped splinters around them.

“I see,” Nehlo muttered. “You have many enemies out there. Because of us?”

“Because ...” Sundance grabbed the Modoc, pulled him to one side, away from the window. “Because of a lot of things.”

“Then,” Nehlo said, “we fight. With you. The war, it seems, goes on.”

Sundance said, “Listen. Let Chachisi and Beneko stay here. Tell them to lay down all the covering fire they can. You and me— You want to go out there with me?”

Nehlo’s brows went up. Then he grinned. “Why not?”

“Tell them, then. Tell them to take this window, that one yonder, keep up a steady fire at every gun-flash. Then wait for me.”

“Yes.” Nehlo nodded, and now his face showed a kind of happiness. He ran his hand along his rifle barrel, then dropped it to the belt around his shabby pants. Sundance saw there the hilt of a knife. “All right. Now I know why you hit me. I do not mind that.”

“Go,” Sundance said. “Tell the others what to do.” He dodged to Wade’s side of the room. Wade was cramming fresh rounds into his Winchester. Susan lay huddled, shielded by the bed’s mattress crumpled over her. Cotton oozed from it where bullets had almost punctured it.

“Wade!” Sundance bellowed. “I’m going out. Me and Nehlo!”

Wade’s face contorted. “Don’t be a Goddam fool!”

Sundance thrust his rifle into Wade’s hand. “Keep up a fire with both weapons. The two Modoc’ll support you.” He ran to the kitchen, hunkered low, scooped up the quiver and bow he’d laid down there. Deftly he notched the string. Then he whipped the hatchet from the sheath, began to chop the floorboards of the kitchen.

“Sundance!” Wade yelled. “What—?”

“I can’t go out the windows or the doors!” He cut three boards through and, muscles straining, ripped them loose from the joists. Nehlo gave Sundance a hand with the last board.

Wolf's Head (A Neal Fargo Adventure--Book Seven)

Wolf's Head (A Neal Fargo Adventure--Book Seven) Hell on Wheels (A Fargo Western #15)

Hell on Wheels (A Fargo Western #15) Sundance 6

Sundance 6 Valley of Skulls (Fargo Book 6)

Valley of Skulls (Fargo Book 6) Apache Raiders (A Fargo Western #4)

Apache Raiders (A Fargo Western #4) Sundance 15

Sundance 15 Sundance 13

Sundance 13 Sundance 3

Sundance 3 Fargo 12

Fargo 12 Sundance 12

Sundance 12 The Black Bulls (A Neal Fargo Adventure Book 10)

The Black Bulls (A Neal Fargo Adventure Book 10) The Sharpshooters (A Fargo Western Book 9)

The Sharpshooters (A Fargo Western Book 9) Panama Gold (A Neal Fargo Adventure #2)

Panama Gold (A Neal Fargo Adventure #2) Alaska Steel (A Neal Fargo Adventure #3)

Alaska Steel (A Neal Fargo Adventure #3) Sundance 7

Sundance 7 Overkill (Sundance #1)

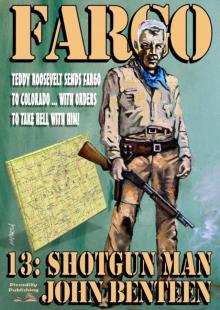

Overkill (Sundance #1) Fargo 13

Fargo 13 Sundance 5

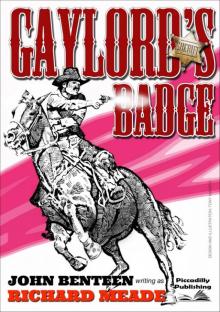

Sundance 5 Gaylord's Badge

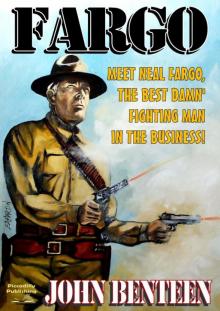

Gaylord's Badge Fargo (A Neal Fargo Adventure #1)

Fargo (A Neal Fargo Adventure #1) The Trail Ends at Hell

The Trail Ends at Hell Sundance 10

Sundance 10 Fargo 20

Fargo 20 The Wildcatters

The Wildcatters The Phantom Gunman (A Neal Fargo Adventure. Book 11)

The Phantom Gunman (A Neal Fargo Adventure. Book 11) Sundance 8

Sundance 8 Sundance 2

Sundance 2 Fargo 18

Fargo 18 Sundance 9

Sundance 9 Sundance 14

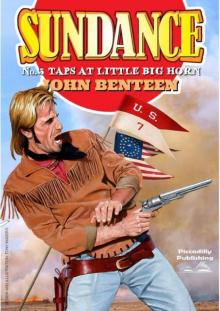

Sundance 14 Sundance 4

Sundance 4 Bandolero (A Neal Fargo Adventure Boook 14)

Bandolero (A Neal Fargo Adventure Boook 14) The Wolf Pack (Cutler #1)

The Wolf Pack (Cutler #1) The Gunhawks (Cutler Western #2)

The Gunhawks (Cutler Western #2) Sundance 16

Sundance 16 Big Bend

Big Bend Sundance 11

Sundance 11 Massacre River (A Neal Fargo Western) #5

Massacre River (A Neal Fargo Western) #5 The Border Jumpers (A Fargo Western Book 16)

The Border Jumpers (A Fargo Western Book 16)