- Home

- John Benteen

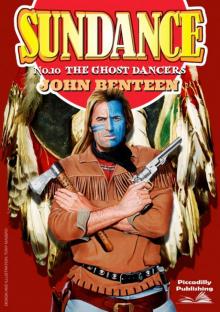

Sundance 10

Sundance 10 Read online

Sundance was called in to try to stop a crazed white-hating Indian from turning the entire western frontier into a bloody no-man’s land. The fanatic Indian had organized the Ghost Dancers, a nation of Indians gathered from every tribe from Canada to the Mexican border.

Driven by the belief that no bullets could harm them as long as they were under the protection of the Great Spirit, they set out to massacre every white man on the plains. It was Sundance’s job to do the impossible and bring peace before it was too late for everyone.

THE GHOST DANCERS

SUNDANCE 10:

By John Benteen

Copyright © 1973, 2016 by John B. Harvey

First Smashwords Edition: January 2016

Names, characters and incidents in this book are fictional, and any resemblance to actual events, locales, organizations, or persons living or dead is purely coincidental.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or by any information or storage and retrieval system, without the written permission of the author, except where permitted by law.

This is a Piccadilly Publishing Book

Cover image © 2016 by Tony Maser

Series Editor: Ben Bridges

Text © Piccadilly Publishing

Published by Arrangement with the Author Estate.

Chapter One

It was a magnificent land and a terrible one, and to love it a man must love also the emptiness of vast spaces where the wind blew free from horizon to far horizon. Once it had swarmed with buffalo, but now they were gone; and as far as Sundance could see, nothing moved on that enormous expanse of Dakota prairie. Remembering how it had once been, with the great dark shaggy herds roaming all across it, followed by Sioux and Cheyennes, themselves as wild as buffalo, he felt a bitterness it was impossible to stifle. Almost, he wished that he, too, could believe in the Ghost Dance, believe that in a few short months Wakan Tonka, the Great Spirit, would send a miracle to the Indians, restoring the buffalo, making the land what it had once had been, driving out the whites who had conquered it.

Then his mouth twisted. There would be no miracles for the tribes. No matter how long they danced, no matter what they believed, no matter how hard they prayed, and no matter how many of them donned their Ghost Shirts, the white soldiers were here, with cannons and Gatling guns, here in force, and they would stay. The Seventh Cavalry was on Pine Ridge, now, with the old score of Little Big Horn to settle, and other regiments scattered across western South Dakota, making a ring of steel around the reservations; this was 1890, not 1876, the year of the great victory at the Greasy Grass, and if there were going to be a war, it would be one the Indians had no chance of winning. Magic was no good against a machine gun... He touched the big Appaloosa stallion with moccasined heels, and the spotted stud, branded with the outline of a Thunderbird on its left hip, increased its pace, devouring the ground with effortless gallop, as if it felt the same urgency as its owner to reach the Pine Ridge Agency.

Its rider was a big man, powerfully built, wide in the shoulders, narrow in the hips. His face was that of an Indian, the color of an old penny, eyes black, restless, continually sweeping the empty land by habit. The nose was a great blade, the mouth wide and thin, chin prominent and strong. But Sundance’s hair, falling from beneath his sombrero all the way to the shoulders of his buckskin shirt, was, by contrast, the color of freshly smelted gold. His Indian features stemmed from his Cheyenne mother; the yellow hair was heritage from his white father.

In his time, he had been many things: Cheyenne Dog Soldier, guerilla fighter in the Civil War, and professional gunman. Now that was behind him, and he was a cattleman, but he still wore the tools of his former trade, for Dakota in November of this year was no place to go unarmed. A Colt was strapped to his right thigh, and on the belt behind it, a long bladed Bowie with a guarded hilt especially made for close-in fighting rode in a beaded sheath. On his other hip was a sheathed hatchet, its handle straight, made for throwing, not chopping; and there was a Winchester carbine in the scabbard under his right knee. Because the weather was unseasonably warm, he had tied his wolf skin jacket behind the saddle; the beautifully fringed and beaded buckskin shirt and the canvas pants and Cheyenne moccasins were enough for now.

In fact, it was so warm that the stud soon worked up a lather, and presently Sundance pulled him up to blow, while he himself rolled a cigarette. Still, on either side, the rolling country was deserted. Then, as he drew in smoke, he tensed, and his hand dropped instinctively to the butt of his saddle-gun, for now he was no longer alone. From a draw to his right a mile away, a file of riders emerged, and, seeing him, made straight for him. He rose slightly in his stirrups, shading his eyes with a hand. The air was perfectly clear, and he had no trouble in discerning that they were not Indians. A moment more, and he recognized them, and his mouth thinned and he put out the cigarette, tossed it away, and loped to meet them. His hand was not on the saddle-gun any longer, but rested on his thigh, close to the holstered Colt.

There were eight of them, and when Sundance was a hundred yards away, they halted, fanning out slightly—white men in range clothes: sombreros, neckerchiefs, chaps and boots, the gear of cowhands. Then two of them detached themselves from the group, trotted forward to meet him: Sundance saw the rifles laid across their saddlebows. As they came up, he said in greeting: “Fain. Hoffman. Howdy.”

“Sundance.” Martin Fain was in his late fifties, a man like a piece of rawhide, his skin weathered, seamed, burnt almost to the color of Sundance’s own by sun. Beneath his flat-crowned Stetson, his hair was silver, and there was a bristle of white mustache above his trap like mouth. His eyes, cold, blue, looked the half-breed up and down as he halted his fine white gelding with the Spanish trappings, silver-mounted and inlaid. In addition to the rifle across his pommel, a Colt was tied down on his chap-clad thigh. When he went on, his voice was dry, harsh, faintly hostile. “Where you bound?”

Sundance sat his saddle easily, relaxed, but his hand stayed close to his Colt as he let his eyes shuttle from Fain to the man on the zebra dun beside him. Joe Bob Hoffman was a Texan like Fain, but a full thirty years younger. He was big and rangy, bigger even than Jim Sundance, with a clean-cut, strikingly handsome face, a white-toothed smile, raven black hair. He was the sort of man women looked at and men liked immediately—until they saw his eyes. Deep-set and gray, they never changed expression, never betrayed warmth, and Sundance, who had seen a lot of Hoffman’s kind, could perceive a kind of madness in them, a contempt and hatred that seemed to encompass every human being on whom Hoffman’s gaze came to rest. It was Hoffman he watched while he spoke to Fain, because Hoffman was the gunman of the pair, with two Remingtons in buscadero holsters deeply cut away around the trigger guards and hung from crisscrossed cartridge belts.

“Headed for the Agency,” Sundance said. “By special invitation of General Miles and General Brooke.”

Fain’s blue eyes shadowed. “They called you in to powwow, too, eh?”

“That’s it. You in on the council?”

Fain nodded “Yeah, Royer asked me to come.”

Sundance looked at Fain’s riders, all armed to the teeth. “You travel with a heavy escort.”

Hoffman laughed, a deep sound “We don’t have the advantage of bein’ half red We’re all white men, you see?”

“Yeah, I see,” Sundance said, letting the mockery in Hoffman’s voice pass.

“Hold it, Joe Bob,” Fain said. He went on. “Sundance. Why did they send for you?”

Sundance shrugged. “Maybe the same reason they sent for you.”

“I hold the beef contract for the agency; that’s why they called me in.” F

ain’s eyes searched Sundance’s face. “And before we get into conference with General Miles and Royer and the others, maybe there’s one thing you better understand. I aim to keep it. If you got any idea of using this meetin’ to try to horn in on it—” The white gelding sidled, and he curbed it. “Well, I’m warning you now, you’d better not recite any more of your lies about me in front of all that brass.”

Jim Sundance’s face lost its faint smile. “Lies, Fain? I’ve told no lies about you.”

“I’ve heard the stories you’ve been circulating—”

Sundance drew in a deep breath. “Fain, with seven men backin’ you, maybe you think this is the time and place to thresh that out. Me, I think different. But I’ll tell you this: if anybody asks my opinion about that contract, I’ll tell ’em the same thing I told the Commissioner from the Indian Bureau. That you’re selling the Agency Texas longhorns at fifty a head—racks of bones you scrape up down on the border, culls there isn’t any other market for. That there’s nothing on those critters for anybody to eat but the skin and bones and guts. And that’s one main reason why the Oglalas and Cheyennes on this reservation are ready to go to war. They need more beef—”

“And you’d love to break our contract and furnish it,” Hoffman turned his horse and now the rifle laid across his saddle pointed squarely at Sundance. “Well, I’ll tell you, Sundance. Our contract runs for damn near a year before it comes up for bids again. You’re welcome to make your play for it when that time comes, but until then, you’d damned well better keep your mouth shut about Fain Cattle Company’s affairs.”

Sundance looked at the rifle muzzle. “Hoffman,” he said, “let me give you a piece of advice. Don’t point that gun at me unless you aim to use it. Because I don’t care what kind of drop you got, I don’t think you can pull that trigger fast enough to keep me from killing you.”

“That’s big talk,” Hoffman said. “A man would have to be real fast … Maybe you were one day, Sundance. But you’re gittin’ old. Me, I don’t think you’re that fast anymore.”

Fain said harshly, “Joe Bob. You put a checkrein on yourself. This ain’t the time or place—”

“Maybe not,” Hoffman said, and the rifle did not waver. “And maybe so.” He was still grinning. “You know, all my life, it seems like, I’ve heard of Jim Sundance. You name it, they say, any weapon, he can take you, gun, knife, that throwin’ ax of his, even a bow and arrer, like an Injun. Then four years ago, damn if he don’t show up here, start that Thunderbird spread of his and try to horn in on our business. Ever since then, I’ve been itchin’—”

Sundance was not watching the gun, he was watching Hoffman’s eyes. There would be, had to be, a fraction of a second’s signal; there always was; nobody could kill another man without betraying his intention that way. And it would be close, but given that much warning—

Then one of Fain’s riders yelled, “Boss. Joe Bob. Hold it. Look ayonder.” And at the same instant, Sundance heard the drum of hoof beats. Still, though, he did not take his eyes off Hoffman as Fain swung his horse. They sat there, watching each other tensely. Then Fain said, “Joe Bob. I said ease off. Soldiers comin’—a platoon.”

There was one more taut second while Hoffman’s eyes, totally devoid of expression save for that intimation of madness flickering deep within them, stayed on Sundance. Then, with knee pressure, he moved his mount and the rifle barrel swung away. Then Hoffman turned his head, and Sundance did the same, and they saw the blue-uniformed men galloping toward them.

Hoffman let out a long breath. “All right,” he said. “It looks like this ain’t the time and place after all. But, remember, Sundance. You been warned. You keep your trap shut in that council about our beef contract.”

Sundance said, “Hoffman, you got the itch. I’ve seen it before. Don’t you crowd me again, or you’ll get a chance to scratch it.”

“Me,” Hoffman said, “I always scratch where I itch. Anyhow, Sundance, you’ve had the gospel word.” Then, so fast it was a blur, he rammed the rifle home in its saddle scabbard and coolly swung his horse. After that, he ignored Sundance as the cavalry approached.

~*~

Watching them come, that short, well-disciplined column, Sundance had to admit that he was glad to see them. He still thought of himself more as fighting man than rancher, and it had been a point of pride not to back down in front of Hoffman. But in a way, Hoffman was right. He, Sundance, was in his mid-forties now, and whether a man liked it or not, by that time he did indeed slow down. Maybe he could have taken Hoffman, maybe not. One thing sure: he could not have fought the whole bunch of Fain’s men.

Of course, he thought, it would probably not have come to gunplay. Martin Fain likely would have restrained his foreman, for Fain was no fool either, and the conference ahead of them was too important to him to complicate with a killing. From Fain’s standpoint, there was a fortune in easy money riding on it; from Sundance’s it was a matter of life or death, not for himself, but for his mother’s people, the Cheyennes, and their allies, the Sioux. But, he knew, it was not over yet, this thing between Hoffman and himself, between Thunderbird and Fain Cattle Company. Far from it. After he said his piece in conference today, the explosion just averted might come anyhow. Well, if so, let it. He was still going to make the offer.

Then the platoon drew up, as the lieutenant in its forefront raised a gauntleted hand in the signal to halt. As the men checked their mounts, the officer trotted his tall bay forward. Sundance, Fain and Hoffman waited, Fain between the half-breed and his foreman.

“Gentlemen,” the lieutenant said. He was, Sundance saw, very young, surely not over twenty-one, and his face was still rounded youthfully, unlined, almost babyish. He was not tall, but he was stocky and someday when he got his full growth, he’d likely be muscular and powerful. Right now, judging from the crispness of his voice, the brisk way in which he touched his hat, he was feeling powerfully the weight of those bars on his shoulders. “Gentlemen. Second Lieutenant Tom Cochrane, Company A, Seventh Cavalry. I’ll have to ask you to state your business—” his eyes swung from Hoffman to Fain, then to Sundance, and all at once his voice changed, turning cool, as his gaze raked over the half-breed—“on the Pine Ridge Reservation.”

“My business is with General Miles and General Brooke,” Fain growled. “I’m Martin Fain, this here’s my foreman.”

“Of course. You’re expected.” Cochrane swung his horse. “And you?” he asked, that coolness still in his voice, his eyes narrowed.

“Jim Sundance from Thunderbird. Miles asked me to come.”

“Sundance.” And now there was definitely hostility in Cochrane’s voice. “Yes. I’ve heard of you.” For a moment, he was silent, and his full-lipped mouth, almost like a girl’s, was petulant, sour. Then he said, with his former briskness: “Very well, gentlemen. We’ll escort you the last five miles to the Agency. We don’t expect any trouble, but no use taking chances. Sergeant Blake.”

A big trooper galloped forward, chevrons gleaming on his sleeves. “Yes, sir.”

“Dispose the men as flankers. I’ll ride with Mr. Fain. You’ll escort Mr. Sundance personally to see that he stays with the column.”

Sundance’s mouth twisted; he needed no explanation of that order or of Cochrane’s hostility. The color of his skin ... To a green officer of the Seventh Cavalry that would be enough to make him suspect. For the Seventh had been Custer’s outfit and there were men among it who had been with Reno and Benteen at Little Big Horn on the day of Custer’s death, men who still felt as if the Sioux and Cheyennes owed a blood debt to the regiment. And who saw in the impending war one final chance to collect it

But he made no protest, preferring to ride apart from Fain anyhow. He held the Appaloosa tight-gathered, as, together with the officer, Fain and Hoffman spurred forward, while the soldiers spread out on either side. The sergeant, having taken care of that, put his mount up next to Sundance’s stud.

“Sundance,” he said “I don’t r

eckon you remember me. I was with Crook after Geronimo down in Arizona.” He was craggy-faced, with a scar running down one cheek and an enormous wad of tobacco bulging the other.

Sundance grinned. “I remember you. You were the Old Man’s orderly for a while.”

“That’s right.” Blake’s voice was rueful. “Twenty years in the Goddamn Army, servin’ with the best damn general ever to wear a star, and now I wind up—” his tone became a whisper “—wipin’ the nose of a shavetail just out of West Point. Ain’t that a case?”

“I figured Cochrane was green,” Sundance said.

“Oh, I reckon he’ll make an officer someday, after he’s had enough of the crap kicked out of him. But you seen how he looked at you and heard that order. Right now he’s achin’ for the smell of powder smoke. Maybe when and if he is ever in a real fight, he’ll feel somewhat different.” Blake spat a long stream of tobacco juice. “Well, it’s been a spell. What you up to these days?”

“Running cattle,” Sundance said. “I’m a rancher.”

Blake looked quizzically at the holstered Colt. “Gave up earning your living with that thing?”

“It paid for a good-sized spread and enough prime animals to stock it,” Sundance said. “A man gets my age and he’s married, he’ll be better off using a lariat and a branding iron.”

“Uh-huh. And they let you get away with that? I mean, first sight I had of you, looked like you and those two Texas fellers had your neck hair up at one another. Ain’t that big one with the two Remingtons Joe Bob Hoffman?”

“You know him?”

“Heard of him, when I was at Fort Davis a spell back. He was a Texas Ranger, and a good one. Only trouble, he didn’t know but one way to bring in his man—feet first. Whether it was a murderer or just a wetback Mexican, he plugged ’em and then served the warrant. Rangers threw him out, and when he kept on killing people invited him to leave the state.”

“That explains it,” Sundance said.

Wolf's Head (A Neal Fargo Adventure--Book Seven)

Wolf's Head (A Neal Fargo Adventure--Book Seven) Hell on Wheels (A Fargo Western #15)

Hell on Wheels (A Fargo Western #15) Sundance 6

Sundance 6 Valley of Skulls (Fargo Book 6)

Valley of Skulls (Fargo Book 6) Apache Raiders (A Fargo Western #4)

Apache Raiders (A Fargo Western #4) Sundance 15

Sundance 15 Sundance 13

Sundance 13 Sundance 3

Sundance 3 Fargo 12

Fargo 12 Sundance 12

Sundance 12 The Black Bulls (A Neal Fargo Adventure Book 10)

The Black Bulls (A Neal Fargo Adventure Book 10) The Sharpshooters (A Fargo Western Book 9)

The Sharpshooters (A Fargo Western Book 9) Panama Gold (A Neal Fargo Adventure #2)

Panama Gold (A Neal Fargo Adventure #2) Alaska Steel (A Neal Fargo Adventure #3)

Alaska Steel (A Neal Fargo Adventure #3) Sundance 7

Sundance 7 Overkill (Sundance #1)

Overkill (Sundance #1) Fargo 13

Fargo 13 Sundance 5

Sundance 5 Gaylord's Badge

Gaylord's Badge Fargo (A Neal Fargo Adventure #1)

Fargo (A Neal Fargo Adventure #1) The Trail Ends at Hell

The Trail Ends at Hell Sundance 10

Sundance 10 Fargo 20

Fargo 20 The Wildcatters

The Wildcatters The Phantom Gunman (A Neal Fargo Adventure. Book 11)

The Phantom Gunman (A Neal Fargo Adventure. Book 11) Sundance 8

Sundance 8 Sundance 2

Sundance 2 Fargo 18

Fargo 18 Sundance 9

Sundance 9 Sundance 14

Sundance 14 Sundance 4

Sundance 4 Bandolero (A Neal Fargo Adventure Boook 14)

Bandolero (A Neal Fargo Adventure Boook 14) The Wolf Pack (Cutler #1)

The Wolf Pack (Cutler #1) The Gunhawks (Cutler Western #2)

The Gunhawks (Cutler Western #2) Sundance 16

Sundance 16 Big Bend

Big Bend Sundance 11

Sundance 11 Massacre River (A Neal Fargo Western) #5

Massacre River (A Neal Fargo Western) #5 The Border Jumpers (A Fargo Western Book 16)

The Border Jumpers (A Fargo Western Book 16)