- Home

- John Benteen

Sundance 16 Page 8

Sundance 16 Read online

Page 8

Covered like that, he was marched through the back door of the saloon and down a dusty street of the little, sleeping town. Ahead, silhouetted against a sky lightening with dawn, was a long, low building, a smokestack protruding upwards from it, a curl of smoke visible against the sky. As they neared it, Sundance saw that on one side was a massive pile of ponderosa pine, brought down from the highlands; on the other, stacks of fresh-cut boards and timbers. The air was redolent with the clean, sweet smell of pitch. In the distance, there was an enormous pile of sawdust.

With Barkalow on one side, Strawn on the other, the rope still around his neck, he was marched into the building, which was really only a roof of shingles on heavy timber posts. He knew almost nothing about sawmills, but he could see how the heavy logs would be rolled down by workers with peaveys or cant hooks, then snatched up and positioned on a long, rolling table by a mechanical arm. That arm was adjustable, to turn the logs for cuts—and further down the table was the saw blade itself, not circular, as he had imagined, but a heavy band saw in a metal frame, a long vertical strap of iron with huge, brutal teeth. And he saw now what would happen to him: he’d be thrown down on the table feet first, and its mechanical movement would carry him straight to the band saw blade. With his legs apart, it would slice through his groin, then up through his belly, split his breastbone like a piece of wood, divide his skull like a sliced melon. His legs went weak, and he staggered slightly. “Barkalow, for God’s sake,” he said thickly.

Barkalow laughed. “Go ahead and beg. It’ll pleasure me, but it won’t do you any good.”

Sundance clamped his mouth shut.

“We won’t need the hook,” Barkalow said. “About four of us’ll hold him down on the table until he hits the saw.” He snapped orders to the Mexicans. “Turn it on.”

“Patron, it is very dull.”

“All the better. I’d hate for this to go too fast. Now, you and you and you—gimme a hand.” Sundance tried to fight, but there was no help for it. They wrestled him down, face up, on the moving table, five yards from the saw—only the table wasn’t moving yet. Strawn stood apart having rolled a cigarette, puffing on it. Sundance fought, and the rope tightened around his neck, cutting off his wind. Strawn turned away, walking up the table to the band saw to stand beside it. Crowbars, cant hooks and peaveys were on racks there.

One of the Mexicans adjusted the boiler pressure. Another, crossing himself, moved some valves. The table beneath Sundance began to vibrate. He tried to fight loose, saw the saw moving so fast it was only a blur, yards away, ready to slice through his flesh and bone.

“Now,” Barkalow said. He and three others held Sundance down. “Just run with the table until he hits the saw. Then dodge if you don’t want to git splattered.”

The black-clad Strawn, puffy face pale, lines deeply etched, stood by the saw-blade, drawing deeply on his cigarette. Barkalow laughed, “Let her rip!”

Then the table was moving beneath Sundance. He fought desperately, but the men holding him were strong. Swiftly he was carried toward that vibrating blade, waiting to slice into his crotch. Once he almost twisted free, then was rammed back down into position, and now the blade was only a couple of yards away. And now, legs spread, it was only a foot distant, his body hurtling toward it. He closed his eyes, braced himself for the excruciating pain—

There was a scream. Not from Sundance, but from tortured metal striking metal. Then the whir of metal fragments, like shrapnel from an artillery shell. And suddenly, though the engine sound continued, the table was still.

Sundance opened his eyes. There was no longer any saw blade. Only jagged fragments, top and bottom, protruding from their clamps. Somebody had rammed a crowbar into the mechanism at the crucial instant, and the saw blade had destroyed itself and the table jammed as the thick, tempered steel had ruined all the mechanisms at the blade. He caught a glimpse of the black-clad Strawn dropping the burnt out cigarette from his lips, grinding it under a black boot.

Barkalow straightened up, face livid. “Beech Strawn! Goddamn you!”

Strawn’s hand dropped away from the jammed crowbar. “I told you, Barkalow, that ain’t no way for a man like Sundance to go.”

Barkalow’s eyes glittered with fury. “It’s the way I wanted it! Damn it, I’ve paid you well and now you’ve turned against me!” His hand made a motion toward his gun.

Strawn’s hand seemed not to move at all, but suddenly his Colt was in it, cocked and aimed, even before Barkalow could touch gun butt. “Don’t you draw on me,” Strawn rasped.

Barkalow’s hand dropped. “But I’m paying you—”

“To kill Sundance and stop the sheep invasion. I aim to do both, but not this way.” Slowly he holstered his gun. “Listen. This ain’t something it’s easy to make a man like you understand. But I’m a man with a certain reputation and so is Sundance. And we’ve just missed crossin’ guns a half dozen times over the years. There are some people who say he’s the best there is. Me, I think I am. But if I let you slice him up with that saw, I’ll never know.” He paused. “Worse. The word will get around. That I was afraid to face him straight-up, gun-to-gun. So I was happy to stand with my hands in my pockets while somebody killed him for me. People will be sayin’ my nerve is gone. And that will ruin my business, the way I make my livin’. This ain’t the first range war I been in, and it won’t be the last. I won’t have my price hammered down because folks say I was afraid to kill Jim Sundance. No. It works the other way. I take him out, my price goes up ... “

He ripped the crowbar from the machinery, threw it aside. “So it’s business, you see?”

“I want him dead,” Barkalow growled. “Right away. With no slip-up.”

“In the mornin’,” Strawn said. “The rest of the night, he gets locked up in the calaboose, tighter’n a drum. He gets some sleep, a good breakfast. Then a gunbelt and Colt with one bullet. I’ll have the same. I kill him, which I aim to do, it’s over. By some fluke he kills me, then you’re free to cut him up whichever way you want to, because you’ll still have him. And my outfit can still handle the Navajos and Delia Gannt for you.”

Seething, Barkalow faced him for a moment, then let his hands drop. “Okay, if that’s the way you want it.”

“It’s the way I want it.” Strawn moved forward, grabbed the rope still around Sundance’s neck. “All right, half-breed. You’ve got your reprieve. On your feet.”

Unsteadily, Sundance slid off the rolling table, careful to avoid the remnants of the broken saw. His knees were shaky, but as Strawn pulled him up close with the rope, he saw his chance, took it. Suddenly he ducked low, then brought his head up hard. His skull caught Strawn beneath the chin; he heard the gunman’s jaw click shut and Strawn lurched backward, knees sagging. Sundance jerked the rope free, taking advantage of the one astounded instant in which nobody moved. Then, as hands flashed for guns, he launched himself in a dive. He hit the ground sprawling, seized the crowbar with which Strawn had jammed the machinery. Coming up, he threw it like a spear, pointed end first. Barkalow bellowed something, ducked. A gunman just behind him screamed as the heavy metal bar buried itself in his face. Sundance rolled again, as guns roared and he heard the ugly whine of lead by his ear. A slug chopped a slice from his left thigh, but no more than a crease, and then he was out of the sawmill and on his feet and running through the little town, zigzagging in the uncertain dawn light. The valley behind him was thunderous, but he gained the shelter of an adobe building.

Never pausing, he ran on, whistling shrilly. Somewhere down the street a stallion neighed full-throatedly. Then hoof beats; Eagle, the reins tied to the hitch rack before the saloon broken, dangling, was pounding toward him. Sundance ran to meet him, hit the saddle without touching stirrup as the big horse stretched itself at full speed. Clinging with one leg around the saddle horn, one hand in Eagle’s mane, he slipped behind the stallion’s neck, no target at all.

“Drop the horse!” somebody yelled, but he’d already turned Eagl

e down an alley between two buildings. Then, wind-swift, the Appaloosa was in the open, pounding across the rolling land of the basin. “After him!” he heard Barkalow yell. “Goddammit, run him down!”

Sundance grinned tightly, eased back into the saddle, gathering reins and bent low. He had his start now, thanks to Strawn’s misplaced gunman’s pride, and he asked no more than that.

They were after him, all right, and coming hard, but they might as well have tried to catch the wind. As dawn peeled back the darkness from the basin, the great wall of the Mogollon rim towered toward the northeast. Sundance aimed the stallion for it, making exactly for the place where Strawn had caught him.

It was a long, hard, bitter run for any horse, and, splashing across the creek, scrabbling up the bluffs, Eagle summoned every ounce of strength he owned—and, the cream of his kind, mountain-bred by the Nez Percé, among the great horse breeders of the world, that was a lot. Gradually the lesser animals of the pursuers fell back, and once Sundance paused briefly, under cover, to give Eagle a chance to breathe. Then he pounded on toward the pinon grove at the foot of the old Apache trail at the bottom of the rim.

It was full light when he reached it, and, turning in his saddle, he could still see them coming, far behind. He grinned—more of a snarl, really, like that of a wolf. Then, coolly taking his time, he searched the grove and presently he found what he sought.

The white men had taken his Colt and Winchester. But they had not been interested in the bow he’d been carrying when they caught him, or the quiver full of arrows they’d made him drop. These still lay where they had landed—and so did the weapons belt, with the revolver gone, but the Bowie and the hatchet still in their sheaths. Quickly Sundance buckled it on, slung the quiver and picked up the bow. Allowing Eagle another single minute of rest, he then put the big spotted stallion up the steep trail.

But not far. A climb like that would break the stud’s heart without more rest than it had had. Besides, Sundance’s blood was hot. Not far up the wall, he reined in, where a ledge cluttered with boulders offered protection. He got Eagle behind the biggest of the rocks, himself sprawled flat behind some smaller ones, jerking arrows from the quiver, laying out a half dozen of them neatly in a row, nocking another to the bow. Then he waited.

And now, slowing, they approached, spread out in a skirmish line. Strawn himself led them, a massive figure in black on a black horse, his rifle at the ready. This time, Sundance knew, there would be no second chance—and yet, in a sense, he owed Strawn a debt, one that could be paid only by meeting him face to face, Colt to Colt. But this was not the time for that right now.

He drew the bow and waited.

They came on, guns up, eyes searching the pinon grove, the huge rock wall behind it. Probably they had forgotten about the bow and arrows entirely, or, not knowing what they could do, discounted them. To all intents and purposes, they were seeking an unarmed man.

Again that wolf’s snarl grin drew Sundance’s lips taut. Five hundred yards, four ... the searchers converged on the foot of the trail. Three hundred yards, he judged. Still he waited. The range closed another fifty. Sundance drew the bow. Then he loosed the arrow. While it was still in flight, he nocked another, aimed and let that one go and reached for another. His movements were swift, deft—for a Cheyenne Dog Soldier could drive home a half dozen shafts as quickly as a white man could empty a revolver’s cylinder.

And the effect below was awesome. The arrows gave no warning of their coming. To the right of Strawn a man threw up his arms and screamed and toppled from his saddle. Almost simultaneously, on Strawn’s left, without a sound, another died, falling forward on his horse’s neck. A third, belly-wounded, howled like a hurt dog and spurred his horse in aimless circles, clutching at the shaft protruding from his paunch. A fourth was lucky; the big flint point only slammed into his shoulder joint and lodged there. His horse reared as he involuntarily jammed home spurs, and then it came down, and he was racing back toward town. The fifth arrow missed its target entirely as a rider turned his horse just in time. And the sixth went exactly where Sundance aimed it, driving home behind the shoulder of Strawn’s black stallion. The horse stumbled, fell, dead before it hit the ground. Strawn, thrown clear, rolled, came up rifle still in hand. But he’d had his warning now, and they were even. Sundance gave him time to drop behind the horse.

Of the dozen men who’d spread out as they approached the pinons, three were dead or dying, one wounded, and their leader unhorsed. And to the survivors, it was as if the finger of God had reached down and wrought its vengeance on them. There was no gun sound, no powder smoke, no way to tell whence those lethal shafts had come, no one to see to fight. He drew another arrow from those remaining in the quiver, lined down on a gunman in full retreat.

Four hundred yards, and the range widening. Still, the bow was part of himself and the morning windless, and the arrow, which he had made, perfect, shaft straight, every feather prime. He drew and loosed.

The arrow caught the man between the shoulder blades. The others saw him fall from the saddle, boot hook in stirrup, body bounce limply as the horse stampeded on. And that was enough for them.

“Let’s get the hell out of here!” somebody roared. Men whirled their mounts, in total panic at the unknown.

“Blake!” Beecher Strawn yelled, and, a gun in each hand, stood up, exposing himself without fear. He snapped off a couple of shots at random toward the wall of the cliff. Sundance answered by sending another arrow. It dug into the ground between Strawn’s spraddled booted feet, and Strawn stared down at it and understood.

“All right!” he bellowed. “Another time, Sundance! You hear? Another time!” Then, as the man called Blake rode up, Strawn holstered his Colts and swung nimbly up behind.

Sundance lay there quietly watching, mouth still stretched in that snarl, as the riders, including the man in black, disappeared at last across the vast reaches of the basin. Satisfied that they were gone, he went to Eagle, rode quickly back down the trail, scooped up a Colt and Winchester from a dead man. Once again fully armed, and with ammo for his weapons, he put the big horse up the wall again.

He let the stallion take its time. It had worked hard today. And besides, he had a lot to think about, a lot to figure out, before he reached the sheep camp.

Seven

“And you mean Strawn actually stopped them from doing that awful thing to you?” There was both horror and incredulity in Delia Gannt’s voice.

Sundance looked at her over the rim of the coffee cup and across the fire. He had been without sleep a long time, now, and his fatigue was almost complete. It had taken him a full day and on into the night to reach the sheep camp in the hidden canyon. Now, having eaten ravenously, he gulped the coffee and felt a certain measure of vigor returning. “He didn’t do it because he’s tenderhearted,” he said harshly. “He did it because he’s losin’ his nerve.”

“Now that I don’t understand,” Andrew McCaig said.

“Because you’re not a professional,” Sundance said. “Especially not one like Strawn.” He searched for the words to clarify his meaning. “The old story about the pitcher that goes to the well too often. Strawn’s been there too often, and he feels the odds turnin’ on him, against him. His nerve’s breakin’ and he wanted some way to reassure himself. Takin’ me out in a straight-up gunfight would have done that for him. It would mean he was still top dog with a gun. That was important to him. It still is. I’ll put it another way, maybe you can understand it, Delia. Maybe a woman is a real beauty and men flock around her. But she starts to get some age on her and the younger competition comes along, and the men don’t flock so much anymore. But if she can take the best, most handsome man around, competition or no, then she don’t feel like she’s gettin’ old after all.”

Delia shook her head. “You gunfighters. You’re a strange breed.”

“If we weren’t all a little crazy, we wouldn’t be what we are,” Sundance said.

“But you don�

�t intend to show Strawn any mercy,” McCaig said.

“No. I aim to kill him. I aim to kill Barkalow, too. The only difference is, I care about how I kill Strawn.”

Delia shivered, not entirely because of the cold mountain air. “But then it was all wasted. Your trip into the Basin. You didn’t really learn anything—”

“I learned a lot,” Sundance said. “All I need to know.”

“Ye mean ye see a chance?” McCaig brightened.

“I see a chance,” said Sundance. “But I’m too tired to talk about it tonight. I’ve got to get some sleep. But first I want to speak to Easy Dreamer—alone.”

“I am here,” a voice said from beyond the firelight.

Sundance got to his feet, staggering with weariness. In the darkness, he spoke softly to Easy Dreamer and the big Navajo nodded. “As you say.”

“Thank you,” Sundance said. “Now I sleep.” And he spread his blankets near the fire, fell into them, head pillowed on his saddle, and almost instantly was totally unconscious.

He was like a wild animal; it did not take much rest to restore him. When daybreak woke him, he was refreshed, fully alert. After breakfast, he saddled Eagle. “I’m riding up creek for a swim,” he told Delia. And added softly: “Alone.”

Her face reddened. “All right,” she murmured. “If that’s the way you want it.”

“This time,” he said quietly and put the stallion into motion.

When he reached the pond, he slipped the stud’s bridle to let it graze, stripped himself completely, his weapons left on the bank with his clothes, and eased into the water, swimming a few powerful strokes, then anchoring one arm to the rock as before and floating, eyes closed, seemingly completely unwary, easing his bruised and aching body in the icy current. Once or twice, though, he shifted position slightly, gaze ranging the thick grove of pines on the left bank of the stream and the boulders piled there.

Wolf's Head (A Neal Fargo Adventure--Book Seven)

Wolf's Head (A Neal Fargo Adventure--Book Seven) Hell on Wheels (A Fargo Western #15)

Hell on Wheels (A Fargo Western #15) Sundance 6

Sundance 6 Valley of Skulls (Fargo Book 6)

Valley of Skulls (Fargo Book 6) Apache Raiders (A Fargo Western #4)

Apache Raiders (A Fargo Western #4) Sundance 15

Sundance 15 Sundance 13

Sundance 13 Sundance 3

Sundance 3 Fargo 12

Fargo 12 Sundance 12

Sundance 12 The Black Bulls (A Neal Fargo Adventure Book 10)

The Black Bulls (A Neal Fargo Adventure Book 10) The Sharpshooters (A Fargo Western Book 9)

The Sharpshooters (A Fargo Western Book 9) Panama Gold (A Neal Fargo Adventure #2)

Panama Gold (A Neal Fargo Adventure #2) Alaska Steel (A Neal Fargo Adventure #3)

Alaska Steel (A Neal Fargo Adventure #3) Sundance 7

Sundance 7 Overkill (Sundance #1)

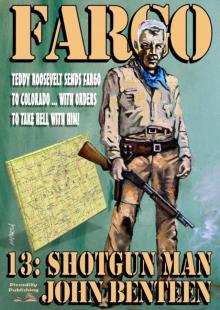

Overkill (Sundance #1) Fargo 13

Fargo 13 Sundance 5

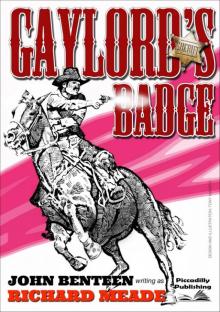

Sundance 5 Gaylord's Badge

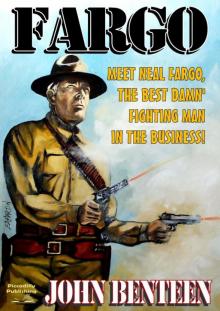

Gaylord's Badge Fargo (A Neal Fargo Adventure #1)

Fargo (A Neal Fargo Adventure #1) The Trail Ends at Hell

The Trail Ends at Hell Sundance 10

Sundance 10 Fargo 20

Fargo 20 The Wildcatters

The Wildcatters The Phantom Gunman (A Neal Fargo Adventure. Book 11)

The Phantom Gunman (A Neal Fargo Adventure. Book 11) Sundance 8

Sundance 8 Sundance 2

Sundance 2 Fargo 18

Fargo 18 Sundance 9

Sundance 9 Sundance 14

Sundance 14 Sundance 4

Sundance 4 Bandolero (A Neal Fargo Adventure Boook 14)

Bandolero (A Neal Fargo Adventure Boook 14) The Wolf Pack (Cutler #1)

The Wolf Pack (Cutler #1) The Gunhawks (Cutler Western #2)

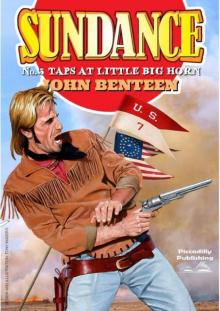

The Gunhawks (Cutler Western #2) Sundance 16

Sundance 16 Big Bend

Big Bend Sundance 11

Sundance 11 Massacre River (A Neal Fargo Western) #5

Massacre River (A Neal Fargo Western) #5 The Border Jumpers (A Fargo Western Book 16)

The Border Jumpers (A Fargo Western Book 16)